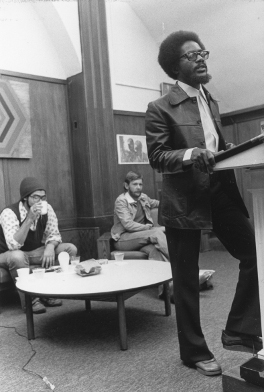

Issa G. Shivji

I grew up in the eastern region of Tanzania,

where I did my primary school. All my secondary school I did in Dar es

Salaam—actually, living in this very apartment. So I grew up here. Then in 1966

I completed my high school, and in 1967 I joined the university. At that time

it was the University College, Dar es Salaam, because it was part of the

University of East Africa. Nineteen Sixty-Seven was an important year because

the year before there had been a student demonstration that opposed the

government’s proposal to start National Service, which was mandatory for

university students. You had to spend about five months in the camps, and for

the next eighteen months 40 percent of your salary would be deducted. Students

opposed it. The president, Julius Nyerere, “sent them down”: expelled them for

a year.

That started a whole rethinking about the

university, and there was a big conference on the role of the university. Then

in February 1967 came the Arusha Declaration.1

The ruling party, the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), issued the

Arusha Declaration and a policy of socialism and self-reliance. Our word in

Kiswahili, Ujamaa (translated as extended family or familyhood), became

the official policy. A number of companies in the commanding heights of the

national economy were nationalized by the government. That started a whole new

debate at the university.

Walter Rodney had just come from SOAS (the

School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London) and became a

young lecturer here.2

In the conference on rethinking the role of the university in now socialist

Tanzania, he played a very important role. So, when I joined the university in

July 1967, it was a campus with lots of discussions and debates in which Rodney

participated.

So that’s my background. From 1967 to 1970, I did my Bachelor of Laws degree in the Faculty of Law. I went to England in 1970 to do my master’s, came back in 1971, and from ’71 to ’72 I did my National Service. Since then, I have been at the university and participated in the various debates and writings.

So that’s my background. From 1967 to 1970, I did my Bachelor of Laws degree in the Faculty of Law. I went to England in 1970 to do my master’s, came back in 1971, and from ’71 to ’72 I did my National Service. Since then, I have been at the university and participated in the various debates and writings.

In 2006, I retired from the Faculty of Law

because we have a statutory retirement age of sixty. But I was appointed the

Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Chair in Pan-African Studies. It’s newly established and

I am the first holder of that Chair. So I am back at the university.

I can’t recall if Walter came before or after

the demonstrations, but he certainly participated in the discussion that

followed after the 1966 expulsion and after the Arusha Declaration. After the

Declaration, in ’67, ’68, there was a small group of people called the

Socialist Club in which Malawians, Ugandans, Ethiopians, and many other

students were involved. The Socialist Club was transformed into the University

Students African Revolutionary Front (USARF). It was all the initiative of

students, not the faculty. Walter was one of the few young faculty involved,

but purely within a relationship of equality. There was no professor and

student there.

The students were very militant, and the

Revolutionary Front, in which I was a member, was led by the chairman, Yuweri

Museveni, who is now the president of Uganda, and a number of other comrades

were involved in the leadership. Then in 1968 we established the organ of the

USARF, which was called Cheche. This was a Cyclostyled student journal

containing many militant articles and analyses of not only Tanzania but the

world situation and the role of young people in the African revolution. In the

first issue, Rodney had an article. He wrote something on labor. I too had an

article, called “Educated Barbarians.” This was our first issue. It actually

became, we realized only later, a very important journal circulated as far as

the United States. There were some study groups anxiously waiting for the

journal to come out. The third issue was a special issue called “The Silent

Class Struggle.” This was a long essay, written by me, which basically argued

that we should not judge socialism simply by listening to what people say, what

leaders say, but by what is actually happening in reality: What are the

relations of production being created and the class interests involved? So, we

worked on the whole question of the development of class and which class is the

agency for building socialism. The issue that followed carried commentary on my

long essay. One of the comments was by Walter Rodney, and after that the

journal was banned and the organization deregistered.

The reasons given were simply that we don’t

need foreign ideology. We have our own ideology: Ujamaa. Cheche is a

Kiswahili word. Translated it’s “to spark.” The Spark was Nkrumah’s

journal, but Spark was a translation from Iskra, Lenin’s journal.

So what the students did immediately after that was change the name to MajiMaji.

Now, MajiMaji is a reference to the first revolt, 1905, of the

people in Tanganyika and the coast against German imperialism. This was called

the MajiMaji War, the MajiMaji Rebellion. The journal continued for some time

after that and continued to publish militant articles. Though USARF was banned,

many of the leaders of USARF took over the TANU League. The TANU League was the

youth arm of the ruling party, and they continued their militant activities.

Ten to fifteen years, beginning in the 1980s,

the last period of Mwalimu Nyerere, and particularly the last five years, were

very critical. We were engulfed in a serious crisis: economic and political.

For the first time, the legitimacy of the political regime was questioned.

Since Mwalimu Nyerere stepped down in 1985, the various policies of his

government have been reversed under pressure from the World Bank, the IMF, and

the donors, particularly from Western imperialism. The 1980s were also the

beginning of the fall of the Soviet Union. One of the sites that were attacked,

ideologically, was the university. The World Bank was telling Africa you don’t

need universities, that they were white elephants, and what you needed to do

was to place emphasis on primary education. The university was starved of

resources. The faculty also began to move out, finding greener pastures either

outside the country or in research institutes, consultancies, think tanks, and

so on. Much of the period of vigorous debates was heavily affected by the

reorientation of the university. The university was turned into a factory to

support and answer to the needs of the market. So faculties of commerce and the

professional faculties became much more dominant. The last fifteen to twenty

years at the university—all the gains of the Nyerere period have been reversed.

One of the objectives of the Nyerere Chair is to try to reclaim to the extent

possible the old debates and to reintroduce and redirect the debates on campus.

In the old period, the international context

was very different. It was a period high on revolution. You had the civil

rights movement in the United States. You had the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War

mobilized young people all over the world. You had the French student

demonstrations. You had the liberation movements in Southern Africa, which were

based in Dar es Salaam and strongly supported by Mwalimu Nyerere. The students

at the university had very close connections with the liberation movements.

Members of USARF went to liberated areas and lived there. All over the world,

there were vigorous debates going on. This was the first decade of independence

in Africa. The whole meaning of independence for Africans was questioned—is it

real independence?—and there was talk about neo-colonialism.

Some of the texts fondly read were Fanon’s The

Wretched of the Earth, Nkrumah’s Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of

Imperialism, and texts by Samir Amin, Paul Baran, and Paul Sweezy.3

These were the kinds of things read, and also classics of Marxism. So the

international context was certainly at a highpoint all over the world. One

interesting example of the kind of contradictory situation we had was a seminar

of East and Central Africa youth organized under the youth league of the party.

It was held at Nkrumah Hall at the university. A lot of our comrades delivered

papers. Rodney also delivered a paper. At that time, there were the hijackings

by the Palestine Liberation Organization. His paper referred to that. It was a

very militant paper about the African revolution and so on castigating the

first independent regimes as petit bourgeois regimes that had hijacked the

revolution. He called it the “briefcase revolution,” where the leaders went to

Lancaster House, compromised, and came back with independence and this was not

real independence.4

This paper was published in the Party [TANU]

newspaper called The Nationalist. Nyerere took very strong objection to

it. The next day the newspaper carried an editorial called, “Revolutionary Hot

Air,” and in very strong terms attacked Rodney for preaching violence to young

people.5

It basically said that while, of course, we were trying to build a socialist

society, our socialist society would be built on our own concrete conditions,

and you cannot preach violence and violent overthrow of brotherly African

governments. He said Rodney is welcome to stay here but not to preach violence

to young people. When that editorial appeared, I remember the morning the

newspapers came out, we read the editorial and all of us suspected, until more

was confirmed, that that editorial was written by President Nyerere himself. We

had prepared this special issue of MajiMaji in which all the seminar

papers would be carried. One of our comrades, when he read the editorial,

became so scared that he took all the papers we had collected and burned them,

and in the process scorched the front grass lawn near the student dormitories.

Then Rodney replied in a long letter, a very

interesting letter. Basically, he defended himself, but he was also appeasing

in that he was thankful and grateful he was allowed to stay here and that when

he talked about capitalism and neo-colonialism he was only talking about that

system which carried his ancestors as slaves into other parts of the world, and

now he was trying to establish a reconnection and talk about this gruesome

system which is still with us.

His famous book How Europe Underdeveloped

Africa was written here. If you look at the preface of that book, there are

two people he thanked personally for reading the manuscript and both of them

happened to be students, Karim Hirji and Henry Mapolu. That was the

relationship we had with Walter. Museveni knew him very well. Museveni was also

a student of political science.

After 1967, one of the important movements

started by the students themselves was that knowledge cannot be

compartmentalized. It’s holistic, and whether you are doing science or law or

political science, the knowledge must be integrated. The Faculty of Law was the

first to start a course called “Problems of East Africa,” in which lecturers

from different departments participated, and Rodney was one of them. That

course then evolved into what was known as a “common course,” which was

compulsory for all the students coming into the university. That further

evolved into what became the Institute of Development Studies and later it

became the Institute of East African Social and Economic Problems. These

were common courses in the formal syllabi. But we the students had our own

ideological classes. We met every Sunday, and we were assigned readings; some

came with readings, made presentations, everyone participated to do what we

called “arm ourselves” ideologically. Again, Rodney was a prominent participant

in these ideological classes. This was totally voluntary. What we read and

discussed was then taken to the classroom. We would not allow lecturers to get

away with anything without being challenged.

So debates continued outside the classroom and

inside the classroom, and there was a close relationship with the liberation

movements. All the important leaders of the liberation movements came to the

university, gave lectures, participated in debates, from Eduardo Mondlane to

Gora Ibrahim of the Pan-African Congress.6

I remember Stokely Carmichael came. C.L.R. James came to Dar es Salaam and gave

fantastic lectures for a whole week. Cheddi Jagan from Guyana came and gave a

lecture.7

East African leaders, including Oginga Odinga, came and gave a lecture.8

The “Front” (USARF) never missed an opportunity. Whatever events took place in

Africa, there would be a statement by the “Front” analyzing and taking a

position on it. The USARF positions were taken very seriously by the liberation

movements. Samora Machel came and talked to the students. There would not be a

single night without some lecture taking place.

There was a time when there was a bit of a

split. This internal division was partly a reaction to the split in

international socialism, between China and the Soviet Union. The Dar es Salaam

campus followed very closely that debate of the Communist Party of China and

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union: the rising socialist imperialism. We

had lots of discussions on that. But many of them were internal splits within

our groups.

This idea that Rodney left Dar es Salaam

because of, or just ahead of, an order to leave—I do not think it’s true. If it

was true, he would have definitely told us. Don’t forget, Rodney left early and

went to Jamaica. From Jamaica he was deported. That’s where he wrote his very

famous pamphlet Groundings with My Brothers. After the riots in Jamaica,

he came back to Dar es Salaam. Then he left in 1974. Now, when he was about to

leave, I remember specifically a personal conversation. We were driving from

the campus, and at the time he and Pat were preparing to leave for Guyana. I

told Walter, I said, “Walter, why do you have to go? Look, stay here. You can

easily try and get your citizenship and continue the struggle. You don’t have

to go back.” He said, “No, comrade. I can make my contribution here, but I will

not be able ever to grasp the idiom of the people. I will not be able to

connect easily. I have to go back to the people I know and who know me.” I

heeded that. That was his position and he left.

Then during the Zimbabwe independence

celebration—he had returned to Guyana and formed the Working People’s Alliance

(WPA) and we closely followed it. On his way to Zimbabwe, and this was a time

when the movement was in trouble, he passed through and stayed with one of our

comrades here. This comrade told him, “Walter stay, don’t go back. Guyana is

dangerous.” There was a case against him in court. Walter said, “No, I cannot

just run away. I have to go back.” So it is certainly not true that he was

pushed out.

It’s more believable that he was pulled

because he felt he could make his contribution there, in Guyana. And he did, in

my view. One can make critical assessments in hindsight, but one of the things

we appreciated, and came to learn from, the Party, the WPA, was how it managed

to bring together Indian and African youth. This was a real breakthrough. Of

course, there were other problems. So my own view is that Walter was not forced

out of Tanzania. It could not be true. If so, we would have known.

Even at that time, while we understood

Rodney’s background, the comrades here sometimes did not fully subscribe to his

positions on race. We often told him that while it was understood in the North

American situation, here it could not be applied. Another issue where we had

strong disagreement was in relation to a piece he wrote called “Ujamaa as Scientific

Socialism.” This was the early seventies. He was trying to show, drawing on the

Narodniks, that Ujamaa is scientific socialism.9

Before he published that, we met and had a discussion on his draft. We had some

heated exchanges and vigorously disagreed with him. We argued that you cannot

identify petit bourgeois socialism as scientific socialism. At the end of it,

Rodney said he would defer to his Tanzanian comrades since we were the ones who

knew the situation here. He went ahead and published it. We did not expect he

would. So what I am trying to say, coming from a different background, is that

we did not accept everything with unanimity.

But we realized Walter was an institution.

Whenever we had differences we met internally and sorted it out. He left a huge

shadow here, on the left, on the African left, and in Tanzania itself. His own

learning and foundation were laid here. When he came to Dar es Salaam, he came

essentially as a young academic from SOAS, where he had just finished his PhD.

His years here were an important period of formation of his own ideas. Like it

was an important period for the rest of us. I think his international fame came

after the book and, of course, was connected with what happened in Jamaica.

I’ll try to be as fair as possible. My own view is there were aspects of

Rodney’s organizational inclination which I think, in a sense, exposed him. Of

course, a powerful movement like that is bound to have enemies. But I am not

quite sure if Rodney always paid enough attention: to a matter of tactics,

number one, and number two, to security of the leadership. It does happen with

powerful leaders like Rodney, the movement tends to become very dependent on

single leaders. That is one lesson to draw. When that leader goes, invariably

the movement falls apart. That’s what seems to have happened in Guyana. While

in theory, of course, we talk about the importance of the movement, importance

of the people, importance of the working people, in practice we always find it

difficult to build movements which can continue regardless of original

leadership.

Of course, I do not know at the moment, and I

keep asking people from there, if there has been a critical assessment of the

WPA. I haven’t seen one myself. I also get the feeling that once Rodney went

and the movement fell apart, even the leaders seemed to disintegrate. I am not

sure if any of them have gone back and tried to reassess it.

While Walter was militant in the Guyana

situation, if anything, the impression I got was that his main contribution was

building a mass movement. I may be wrong. But I always took the WPA to be a

mass movement and not an underground conspiratorial group. If at a certain

point the WPA, after assessment, reached the conclusion that there was no other

way except armed struggle, I don’t know. I never really came across an

assessment. But certainly, from what we know and the way it operated, the image

I have of the WPA is of Rodney as its collective leader. Another very

interesting contribution of the WPA: collective leadership, with all the mass

of youth behind them, walking the streets, going to a sugar plantation. This is

the image I have of the WPA. That image is not totally consistent with some

kind of conspiratorial group and armed struggle.

But there are two aspects, particularly for

the period we are going through now: collective leadership and a mass movement

are important contributions, something to learn from. Not to ignore the

circumstances connected with armed struggle, but I think one thing we have

learned is that armed struggle alone, without a mass movement, has a tendency

to deteriorate. And once again the importance of politics rather than

militarism is coming back. I remember in the early eighties I was on a lecture

tour in the United States and Canada, and the point I kept emphasizing was that

the period we were going through in Africa then was essentially a period of the

insurrection of ideas, insurrection of mass movements, open mass movements,

rather than underground armed struggle groups: in other words, insurrectional

politics. To a certain extent we saw insurrectional politics in the movement

that started after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the so-called democratization

movement. In West Africa and elsewhere, it became a mass movement.

Of course, it was suppressed, preempted; it

was hijacked in many ways. What was essentially insurrectional politics for

real democracy was hijacked into multi-parties. Multi-parties is not the

end-all of democracy. The liberal Western model cannot simply be adopted, in my

view. But those ten to fifteen years of liberal politics and neoliberal

economics, I think, are coming to an end. The neoliberal honeymoon is over.

Interestingly, there is a whole new, other way of thinking.

Let me give you my own experience in this

country. In the few events I organized under the Nyerere Chair, it’s amazing to

see how young people want to know more about where we are coming from. For that

purpose, today, we are beginning to see people talking about the historical

experience, talking about Ujamaa. At one time, Ujamaa had become a term of

abuse. Nyerere used to say, “If I was to talk about Ujamaa openly I would be

considered a fool. I can only whisper about it.” But now these ideas are coming

back. They are being recalled. In my view, the whole imperialist, neoliberal

onslaught is coming to end. Of course, it won’t happen tomorrow. But it doesn’t

hold the same ideological pull it once supposedly held. There is a lot of

rethinking going on in the world. All over Latin America we are witnessing it.

So it’s an interesting period.

Now, I don’t think we can repeat or just

reclaim the past, of course, but we will learn from it and people will want to

know where we are coming from.

The current situation in Africa also points to

some of the problems of old and the old debates we had. While individuals play

an important role, individuals do not necessarily characterize the whole

movement. Individuals do get transformed once they get into power. A very good

example is our own Yuweri Museveni, who was a militant, a Fanonist actually,

during his student days and what he has become subsequently. I think to

understand it much more we must view it in terms of the social, political,

economic forces of the time. In the case of Mugabe, we have to go back to

history. ZANU’s (Zimbabwe African National Union’s) accession to power was a

kind of compromise. In which some of the African leaders I know of were

involved, including Nyerere. They pushed ZANU to accept that compromise. You

will notice—and more work has to be done on this—that in the case of liberation

movements at very critical times in South Africa and Zimbabwe, some of the

important leaders held a clear vision of what they wanted their societies to

be. These leaders were bumped off: Hani in the ANC (African National Congress)

and, in Zimbabwe, Herbert Chitepo.10

When the leaders came to power, they inherited

the state structures. Look, for example, at Zimbabwe. The “Lancaster

compromise” meant that for ten years they could not touch the land occupied by

white settlers. Land was the leading issue for which the people fought. And Mugabe

did not take action. The new people who came to power began to develop

themselves into a class of their own, so to speak. The land question had to be

addressed. But by the time Mugabe addressed it conditions had changed affecting

the way he finally addressed it, that led to the situation we are in—to the

extent that now you cannot even mobilize your own people to support your

anti-imperialist stand. So anything said is just rhetoric. There are complex

issues of how those leaders addressed those issues. Particularly in Africa, we

notice that when progressive leaders come to power, they find themselves in

difficulty because they are not rooted in the people and do not take their

messages from the people. Without knowing the pulse of the people, they immediately

become alienated. They become prisoners of the structures they inherited.

So there is a lot to be said about movements

that may look protected, confused, but are movements from below. It remains to

be seen to what extent the left, or revolutionary elite, will learn from that

movement, integrate themselves within it, before they claim to know and to

teach. There is a lot of learning, a lot of learning, to be done.

Issa G. Shivji is the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Chair at the

University of Dar Es Salaam, and hosts the annual Mwalimu Julius Nyerere

Intellectual Festival. This essay is adapted from the new Monthly Review Press

book, Water A. Rodney: A Promise of

Revolution, edited by Clairmont Chung. The book is comprised of

oral histories by academics, writers, artists, and political activists who knew

the great writer and revolutionary, Walter Rodney, intimately or felt his

influence.

Notes

1. ↩ The Arusha Declaration is a manifesto that

offers guidelines for the practice of a brand of ethics that promotes equality

and mutual respect informed by African history and culture.

2. ↩ University of London, School of African and

Oriental Studies.

3. ↩ Frantz Fanon, was a Martinique-born,

French-trained psychiatrist who described the psyche of oppression and the

coming revolution in his books; Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah was Ghana’s first

president, founder of the Non-Aligned Movement, and a father of the Pan-African

movement; Samir Amin is a noted Egyptian economist and head of CODESRIA, based in

Dakar, Senegal; Paul A. Baran was a Stanford University professor of economics

known for his Marxist views, who wrote The Political Economy of Growth (New

York: Monthly Review Press,1957); and Paul M. Sweezy was a Marxist economist,

political activist, publisher, editor, and founder of the magazine Monthly

Review.

4. ↩ Lancaster House, situated in West London and

once part of St. James’s Palace, is used by the foreign affairs department to

host talks. It hosted the Zimbabwe independence talks as well as Guyana’s.

5. ↩ The Nationalist, in its December 13, 1969,

editorial quoting Rodney’s paper said, “The Paper stated that ‘armed struggle

is the inescapable and logical means of obtaining freedom’ and that

independence which was achieved peacefully could not, by definition, be real

independence for the masses.” Reprinted in Chemchemi: Fountain of Ideas 3

(April 2010).

6. ↩ Born in Mozambique, Eduardo Mondlane attended

college and graduate school in the United States. He returned to the region and

was elected president of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), which was

formed in Tanzania, and served until his assassination in 1969. After

independence in 1975, the university in the Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, was

renamed Eduardo Mondlane University. Ahmed Gora Ebrahim served as secretary of

the PAC’s department of foreign affairs. The Pan-African Congress was seen as a

“black consciousness” prong in the movement to end apartheid in South Africa.

7. ↩ Cheddi Jagan was the first premier of Guyana

and led the movement for independence through the People’s Progressive Party

(PPP). The party split in 1955. Forbes Burnham led the exodus and formed the

People’s National Congress (PNC). With assistance from the United States and

Britain, Burnham became premier in 1964 and led the negotiations for Guyana’s

independence, which came in 1966.

8. ↩ Kenyan freedom fighter Oginga Odinga served

briefly as vice president under Jomo Kenyatta but resigned after differences

with him. He continued in political life despite being jailed and often

detained by Kenyatta and his successors.

9. ↩ The Narodniks represented a school of thought

that originated in Russia sometime in the 1860s. They saw the peasantry as the

revolutionary class that would overthrow the monarchy, and the village commune

as the embryo of socialism, but believed the peasantry required a middle class

or its equivalent to help engineer the revolution.

10. ↩ Chris Hani, a lifelong member of the African

National Congress in South Africa, was assassinated in 1993 by right-wing

opponents of the ongoing negotiations to end apartheid. Hani once headed the

ANC’s military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe. Herbert Chitepo, a huge figure in the

Zimbabwe liberation struggle and the ZANU in particular, died on March 18,

1975, in Lusaka, Zambia, when a car bomb exploded. It killed him, his driver,

and a neighbor. He was the first black African qualified as a barrister in

(then-named) Rhodesia.

Remembering Walter Rodney acknowledges the legacy of the prominent Guyanese historian, activist, and scholar. How Design Game Rodney's work focused on African history, Pan-Africanism, and the struggles for social justice. His influential book, "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

ReplyDeleteGreat reading yyour blog post

ReplyDelete